Soil Babies by Ken Rinaldo and Amy Youngs was a crowd-sourced edible sculpture intervention created with a group of artists who wanted to learn about compost and soil regeneration. Together, we designed a “worm bassinet,” an art-science cradle for red wriggler worms, where miniature edible sculptures were placed as both nourishment and art. Over time, these sculptures were deconstructed by the worms, turning ephemeral art into rich compost. This process simultaneously fed the worms and enriched the soil, while also nourishing a community’s awareness of vermicomposting as a regenerative practice—one that addresses climate change and promotes healthier ecosystems.

The work embodied an interspecies collaboration, bringing together human artists, worms, and the vast bacterial cultures that inhabit the worms’ microbiomes. These gut microbes play a vital role in decomposing organic matter, breaking down complex plant fibers, and creating nutrient-rich castings that enhance soil fertility. Recent studies have shown that earthworm digestion stimulates beneficial microbial activity, increasing the bioavailability of nitrogen and phosphorus, which are critical for plant growth.

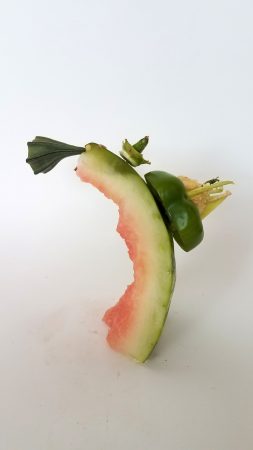

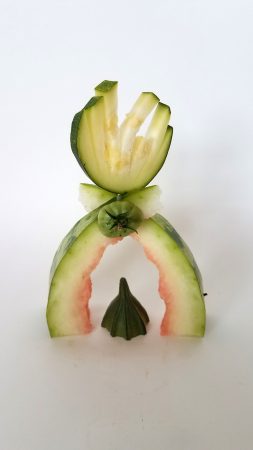

Our process began with locally sourced organic waste—waste paper, watermelon rinds, and vegetables grown on-site. We hand-crafted these materials into small sculptures, each a unique form designed to invite both human contemplation and worm consumption. These sculptures were placed in the bassinet for the worms to consume over days and weeks, allowing their slow transformation to be both a visible and an ecological act.

This work addressed one of the major environmental challenges of our time: methane emissions from landfills. Methane, a potent greenhouse gas, has a global warming potential more than 25 times that of carbon dioxide over a 100-year period. According to recent research, organic waste in landfills is responsible for at least 17% of global methane emissions. By diverting organic matter into small-scale vermicomposting systems, we can significantly reduce these emissions while creating a closed-loop system of nutrient cycling.

Red wriggler worms (Eisenia fetida) are particularly suited for this kind of work. They thrive in contained environments, rapidly process organic waste, and produce “worm tea,” a nutrient-rich liquid fertilizer. In our bassinet design, the baby’s arm and foot collected this worm tea, symbolically linking human care to ecological care. This tea, rich in beneficial microorganisms, can improve plant immunity and enhance soil microbiome diversity.

The project also used technology to bridge art, science, and public engagement. A Raspberry Pi and miniature camera system were installed to livestream the worms’ interaction with the sculptures. Gallery visitors could watch in real time as worms nibbled, tunneled, and slowly integrated the sculptures into the living soil. This act of witnessing made the normally hidden processes of decomposition visible, reframing decay as an act of creation.

Once the exhibition concluded, the enriched soil and worms were returned to the farm on the gallery site, where they continued their work in a larger ecological context. This closed-loop approach mirrors regenerative agricultural practices, which emphasize building soil health rather than depleting it. Recent research into soil microbiomes underscores that a single teaspoon of healthy soil can contain up to one billion microorganisms, representing thousands of species—fungi, bacteria, archaea, and protozoa—all interacting in a complex web of nutrient exchange. Worms are keystone species in this network, enhancing microbial diversity and facilitating carbon sequestration.

Ultimately, Soil Babies was both an artwork and an ecological intervention. It invited participants to see themselves as part of a living, interdependent system, where waste is not an end but a beginning. The project encouraged a shift in perspective—from seeing soil as inert matter to recognizing it as a vibrant, intelligent community. What we eat and discard can become food for others—worms, microbes, and plants—continuing a cycle that sustains life across species and generations.

Exhibitions

VISIBLE RECORDS Charlottesville, Virginia, Aug 1-Sept 13

The Tihua Tocha Exhibition invites The Weight of Sunshine mobiles, stabile sculptures along with the Soil Babies by Ken Rinaldo and Amy Youngs, and version two of Angel of Car of Death (Carro Angel de Muerte) invited and curated by Federico Cuatlacuatl.

References:

- Dume, B., et al. (2021). Carbon Dioxide and Methane Emissions during the Composting and Vermicomposting of Sewage Sludge… Atmosphere, 12(11), 1380.

- Hwang, H. Y., et al. (2022). Addition of Earthworm Castings Reduces Gas Emissions and Improves Compost Quality. Applied Biological Chemistry, 65, 27.

- Impact of Vermicomposting on Greenhouse Gas Emission: A Short Review (2025).

- Nature Communications (2023). Earthworms Do Not Significantly Contribute to GHG Emissions in Agricultural Settings.

- High‑Temperature and Earthworm Combined Composting Reduces Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Waste Management / SSRN (2023).

- Emission of Greenhouse Gases during Composting and Vermicomposting under Varying Conditions. ScienceDirect (2022).

- Henderson, Tamara. (2023). An Artist’s Ode to Worms. Hyperallergic.

- Ecological Art That’s Literally Alive. Hyperallergic (2025).

- Sekules, Veronica. (2024). Starting to See Waste as Art and Heritage. ClimateCultures.

- UNCG and Guilford College Collaborative “Compost” Exhibition (2024).

- GWENBA. Dreams of Vermi‑Computing & Other Monsters. Art Gene.

- McAllister, Lorrie (with Amy Youngs). Worm Culture Art.

- Aloi, Giovanni. Nature in Visual Culture; Antennae and Ecological Art Critiques.

- Fowkes, Maja & Reuben. Art and Climate Change. Thames & Hudson (2022).

- Brookner, Jackie. Biosculptures: Living Soil/Water Ecosystems as Public Art.