The Symbiogenesis installation examines and deciphers the early invasion of the cell, tracing back billions of years to fundamental evolutionary events. This work explores the complex transitions between invasion, parasitism, and eventual symbiosis—critical processes that have shaped life itself. As a multispecies entity composed of human and microbial cells, we embody the legacy of these ancient biological integrations.

At its core, the installation engages with Lynn Margulis’ pioneering concept of symbiogenesis, which challenges traditional notions of individuality and selfhood in evolutionary theory. Symbiogenesis posits that mitochondria—energy-producing organelles in most animal, plant, and fungal cells—originated when an ancestral eukaryotic cell formed a mutually beneficial relationship when it engulfed an aerobic bacterium, likely an alphaproteobacterium, over 1.5 billion years ago.

This event did not lead to digestion but to coexistence, fundamentally altering the trajectory of life. Today, mitochondria remain distinct entities within our cells, possessing their own DNA, reproducing independently, and driving essential metabolic processes, such as ATP synthesis through aerobic respiration.

Visualization and Interaction

This art-science installation seeks to render these ancient symbiotic beings visible through large-scale fine art glass sculptures, robotics, and interactive elements. Sensor-based interactions, miniature cameras, and projected imagery will create dynamic, immersive environments that reflect the life and agency of mitochondria.

Among unicellular eukaryotes, the number of mitochondria can vary from 1 to ~100,000, and this depends on the specific organism. Grape vines in the growing season have 25–50% more mitochondria than in the autumn, and much depends on the life stage of the organism. The HeLa human cell line can have ~300 or ~800 mitochondria at different times, depending on whether it’s going to divide, and it depends on the life stage of the cell.

Mitochondria hold a unique genetic inheritance, passed primarily from mother to child, with rare instances of paternal contribution. These organelles, once independent bacteria, now reside within us as vital components of our cellular function and consciousness. Their presence challenges the singular notion of the self, as nearly half of our bodily cells are bacterial, actively participating in our biological and cognitive processes.

Machine Consciousness and Symbiosis

The installation further explores the parallels between biological and technological symbiosis, particularly in the era of artificial intelligence. As our digital networks intertwine with human cognition, we may be witnessing the emergence of a new form of machine consciousness—a crude but evolving intelligence shaped by vast datasets, neural networks, and human desires.

The concept of the supraorganism emerges, wherein humans, mitochondria, and artificial systems form a layered, interconnected entity.

Lynn Margulis’ intellectual journey—her challenge to Darwinian “survival of the fittest” in favor of cooperative evolution—provides a guiding framework for this work. Her writings, along with those of her son Dorion Sagan, particularly Into the Cool: Energy Flow, Thermodynamics, and Life by Eric D. Schneider and Dorion Sagan , inspire sonic elements in the installation as the work and writings of American astronomer, planetary scientist and science communicator Carl Sagan. Their explorations of the second law of thermodynamics and its role in life’s emergence underscore the significance of energy flow, organization, and information in evolution.

Multi-Sensory Experience

The installation features: Beakers containing vortexes of water, amplified through miniature cameras, and projected onto walls, creating a visual dialogue between microscopic and macroscopic worlds. Vortexes of water are dissipative structures as referenced by Nobel Laureate Ilya Prigogine.

The turbulence at the bottom of the beakers allows a persistent spiral to form. Self-organization in dissipative systems. This is closely related to Prigogine’s work, which showed that non-equilibrium conditions (such as energy flow through a system) can lead to the emergence of stable, structured patterns.

Dissipative structures share key properties with living systems—they sustain themselves by consuming energy, maintain a structured form, and respond to external conditions.

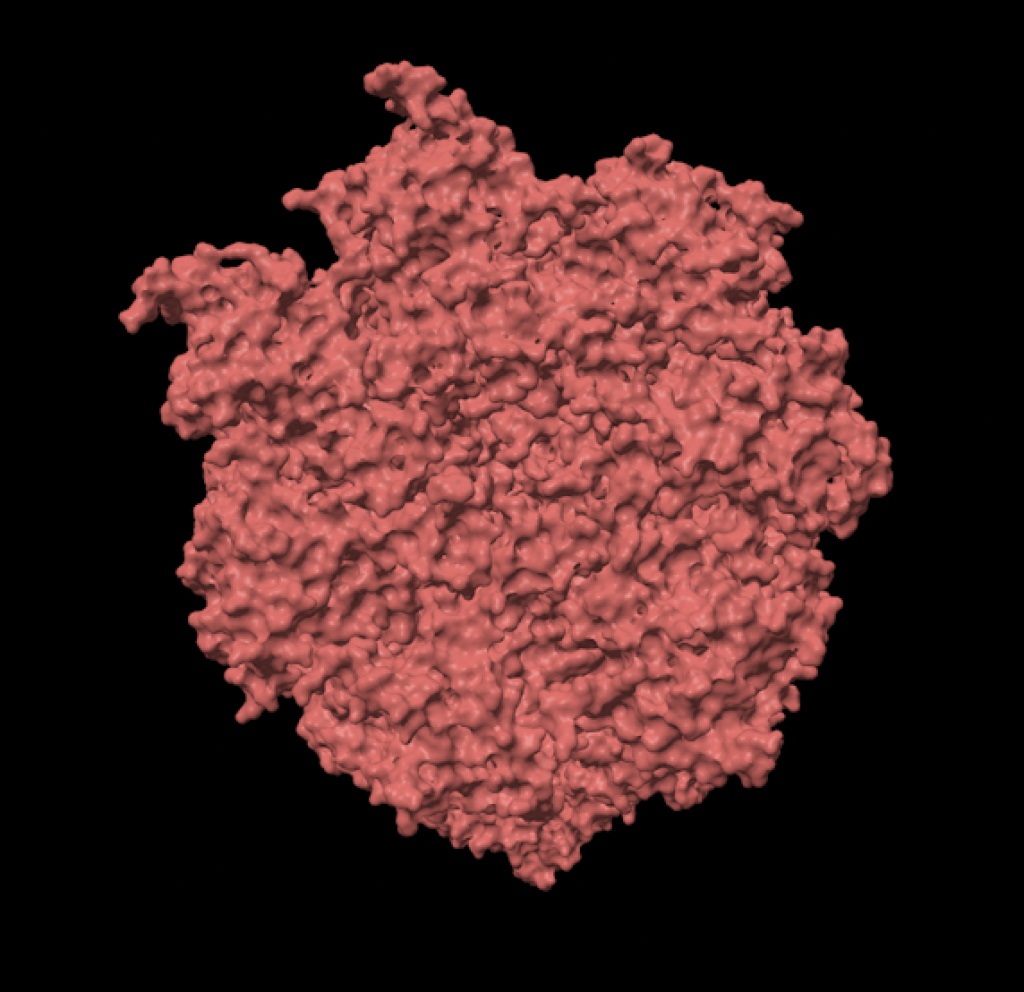

While these self-organizing structures do not represent life in a biological sense, they exhibit fundamental characteristics of living systems, such as organization, adaptation, and persistence—leading to interesting discussions about the origins of life and complex systems. In some of these dissipative structure’s images or protoribosomes ribonucleic acid images are behind them with laser light referencing sunlight (energy input) on the Protoribosomes and RNA images. Protoribosomes (precursor-like structures to ribosomes) existed in some primitive form in space is speculative and intriguing.

Ribosomes themselves are highly complex biological nanomachines responsible for protein synthesis, and their evolutionary precursors—protoribosomes—likely arose through simpler, chemically driven self-assembly processes on early Earth. The concept that their initial building blocks or even primitive RNA-based scaffolds originated from space via amino acids has attracted interest and research.

Telescopes and microscopes referencing both Margulis’s microbiological research and Carl Sagan’s astronomical inquiries, emphasizing the interconnectedness of knowledge across scales are also present. As you look into some of the telescopes you will see animations of kinesins or motor proteins walking on the cytoskeletons of the cell.

A computer-generated voice will be reading AI generative texts, composites of Lynn Margulis, Carl Sagan and Dorion Sagan will all be heard from within the mitochondrial sculptures, and some dishes will have red cherry shrimp, mosses, and ferns presented; all life coexisting with Mitochondria.

Alpha Fold and the Next Stage of Evolution

The installation extends into the present and future with references to Alpha Fold, an AI system developed by DeepMind that predicts protein structures with unprecedented accuracy. Alpha Fold’s breakthroughs in protein folding have profound implications for biology, medicine, and synthetic life, offering insights into the intricate molecular machines that sustain life.

By accelerating our understanding of biological processes, AI-driven discoveries like Alpha Fold contribute to a new evolutionary phase—one where human intelligence and artificial intelligence co-evolve, shaping the next frontier of life itself.

A central visual element of this installation will be a projection of a bacterial cell motoring through the cytoplasm, dynamically constructing and deconstructing the actin cytoskeleton as it moves. It may also include cuts to an animation of the mitochondria showing ATP synthesis.

This visualization underscores the perpetual transformation within cells, mirroring the broader themes of emergence, adaptation, and symbiosis.

Symbiogenesis 2025-26 is a meditation on the intertwined narratives of biology, technology, and cognition and the emergence of life itself.

Through art and science, it invites audiences to reconsider the nature of individuality, agency, and evolution in an era where humans, microbes, and machines form an unprecedented symbiotic network.

As we stand at the threshold of new forms of intelligence, the installation prompts reflection on what it means to be alive in a world where biology and technology continue to merge.

Production and Special Thanks

The University of Texas and Dr Charissa Terranova for their financial support of this installation and for the world wide premiere at the SP/N Gallery

I have deep gratitude for the Glass Community in Ohio; especially at The Ohio State University and beyond, and the many great artists and professors they have fostered internationally. How did this happen? Professor Richard Harned and Ruth King!

Gayle Van Marter below working on the cold-working of the mitochondrial forms

I am forever grateful for her expertise and patience in this process.

Danner Seyfer Sprauge for working with me on 3D modeling these visualizations and for production on the printing and massaging of the proteins walking on the mitochondria, the sound circuit holders and many 3D printed parts.

Trademark Gunderson for his robotics and debugging expertise on the sound circuits including the Raspberry Pi

Dorion Sagan for reviewing my text for the soundtrack of one of the mitochondrial works, and finding a critical mistake about the second law of thermodynamics. We entered into a long and fruitful discussion online, and I am thrilled he offered his critical feedback and has also agreed to show a drawing work and poem near the acknowledgements section where we will celebrate him, his mom Lynn Margulis and Dad Carl Sagan.

Joshua Gagliardi for laser cutting, The College of Nursing, Laboratory Research Operations Senior Analyst

Zack Sanderson for laser cutting, The Department of Art The Ohio State University

The Ohio State University Emeritus Academy for the Faculty grant to help pay for the cold-working and necessary equipment

Zach Sanderson for Laser Cutting, The Department of Art SADR Digital Fabrication Lab Specialist

EXHIBITIONS

SP/N GALLERY Dallas, Texas, Feb 7-Apr, 2026

Organic Worlds: Symbiogenesis in Art presents the World wide premiere of Symbiogenesis, and Anicca Antennae-Soil as Brain; robotic beings, as avatars to insects, soil and bacteria as well as The Evolution of Information = Life, Organic Murmuration, SIGNS, The Farm Fountain, 3 Story Robots. Two person exhibition with Amy Youngs. Invited by Professor Dr Charissa Terranova.

References

Lynn Sagan, On the origin of mitosing cells, Journal of Theoretical Biology, Volume 14, Issue 3, 1967, Pages 225-IN6,

https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(67)90079-3

Kozo‑Polyansky, B. (2010 English Translation of 1924 Original). Symbiogenesis: A New Principle of Evolution (Ed. Mikhailov, V. & translated by Sym, S.). Harvard University Press. https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674054095

Mereschkowski, K. (1910). The theory of two plasms as the basis of symbiogenesis, a new principle of biology. Biologisches Centralblatt, 30, 278–288. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Konstantin_Mereschkowski

Aanen, D. K., & Eggleton, P. (2017). Symbiogenesis: Beyond the endosymbiosis theory? Current Opinion in Microbiology, 43, 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2017.01.007

Martin, W. F., et al. (2015). Endosymbiotic theories for eukaryote origin. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1678), 20140330. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0330

MIT List Visual Arts Center (2022). Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere. Exhibition catalogue. https://listart.mit.edu/exhibitions/symbionts-contemporary-artists-biosphere

Chen, X., et al. (2025). Symbiosis of Agents: Co-Evolution of Embodied Agents via Environmental Feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.02606. https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.02606

Schubert, T., et al. (2014). ChromaPhy: A Living Wearable Connecting Humans and Their Environment. arXiv preprint arXiv:1403.6823. https://arxiv.org/abs/1403.6823

Prigogine, I., & Stengers, I. (1984). Order Out of Chaos: Man’s New Dialogue with Nature. Bantam Books. https://archive.org/details/orderoutofchaosm00prig

Neyrinck, M. C., et al. (2020). As Above As Below: Cosmic–Cellular Structural Parallels. arXiv preprint arXiv:2008.05942. https://arxiv.org/abs/2008.05942